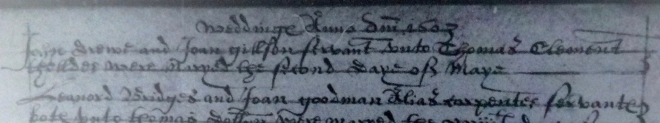

On 26th February 1843, Stephen Bumstead married Phoebe Ann Gait at St Mary’s Whitechapel in the east end of London. Stephen described himself as a plumber & glazier, and a widower, the son of another Stephen Bumstead, also a plumber & glazier. They both signed their names (Phoebe signed Phebe Ann Gaitt) and the witnesses were Mary Ann Bumstead and Henry Chapman. As we have seen (here) Stephen moved to London from Ipswich, where he was a Freeman and where his family had practiced the same trade for several generations. Mary Ann was his sister-in-law, wife of his brother William Wase Bumstead and a Henry Chapman appears in the 1841 census with the same occupation as Stephen, so he may be a colleague.

Prior to his marriage to Phoebe Stephen had been married to Elizabeth Kennedy who had died in 1838 and he seems to appear in the Census three years later where there is a Steven Bumstead, living at 57 Chiswell Street, Finsbury, sharing accomodation with Hannah Maguire. This Steven gave his occupation as “painter” and Hannah was a servant. The ages in that Census, unlike later ones were rounded down for adults to the nearest 5 years. Steven is shown as being 30, so he could have been 34, but he was in fact 39, if this is our Stephen. Hannah was 20. The next property listed on the Census is 95 Milton Street and interestingly our Stephen Bumstead gives his address as 96 Milton Street on the marriage certificate of 1843.

The first child of Stephen and Phoebe, a son also named Stephen was born on 14th January 1844 at 41 Betts Street, near St George’s Church in Stepney. Stephen’s occupation on the birth certificate is given as a painter.

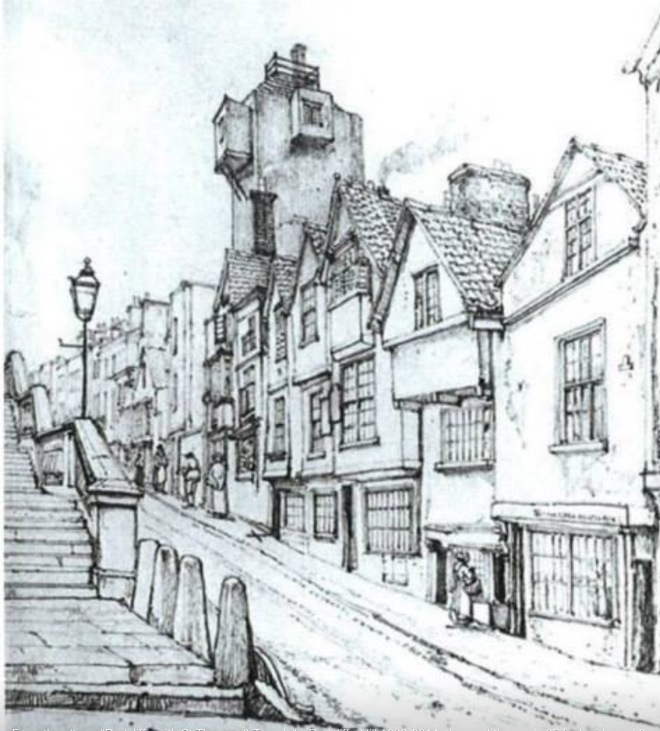

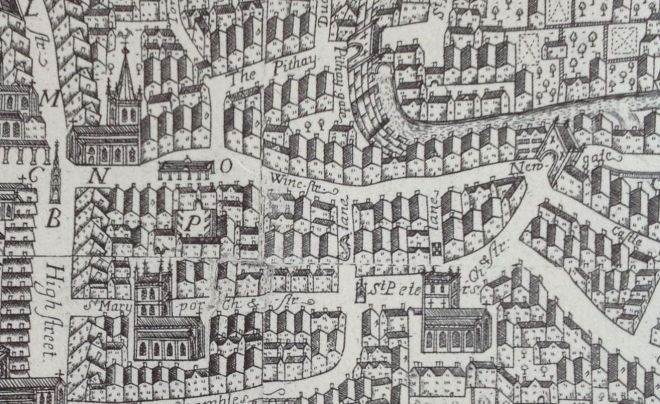

Old Montague Street, Spitalfields

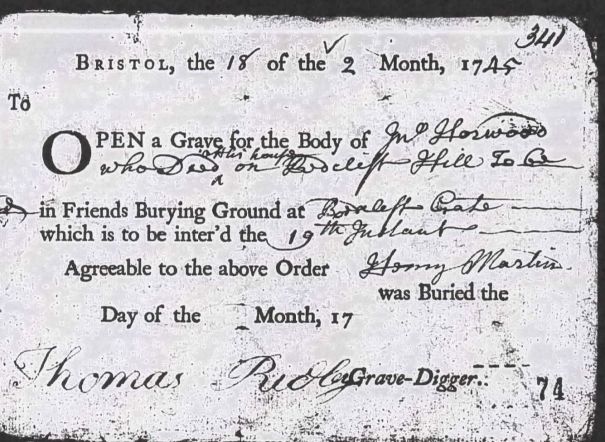

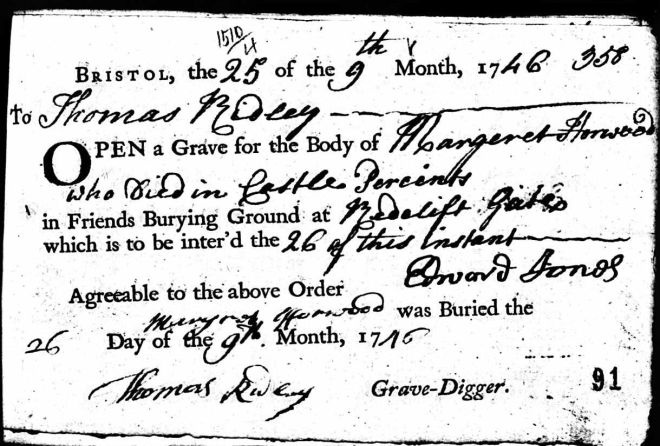

Stephen senior died on 31st May 1846 of Typhus Fever. His age is given as 46 and the family had moved north to Old Montague Street in Spitalfields. On the death certificate Stephen was given as a painter and glazier. He was buried in the churchyard of Christ Church, Spitalfields on June 3rd. Phoebe was by then expecting a second child; a daughter was born on September 28th and she was given the name Georgina Ellen Gait Bumstead at the registration of the birth the following month. Poor Phoebe was to suffer further grief as baby Georgina died at the age of 8 months on 22nd June 1847, and she too was buried at Christ Church. By then Phoebe appears to have remarried for she signed her daughter’s death certificate Pheby Ann Rogers.

Christ Church, Spitalfields

Although Phoebe still gave her Spitalfields address on Georgina’s death certificate, the baby actually died in Tranquil Vale, Blackheath. There is no obvious family connection to the area, but it is interesting that there was, at the time a family named Bumstead living in Blackheath Vale. The 1841 census shows a Mary Ann Bumstead and a daughter, Eliza and son Edward. Further searches have revealed that a Stephen Bumstead married Mary Ann Swain at St Margarets, Lee on 9th December 1811. Their children were baptised at St Alpheges in Greenwich in the succeeding years. This Stephen died in 1838.

Phoebe had not in fact remarried but had moved in with a George Rogers, who was almost certainly a cousin. He too had been in London for some time, although coming originally from Somerset, like Phoebe. His first wife had recently died, leaving him with a young son, another George. Although living together since 1847 and having several children, they did not finally marry until 1856. The story of Phoebe’s ancestors is told here and her personal story here.

George and Phoebe Rogers stayed in London for a short time, a daughter whom they also named Georgina Ellen Gait Rogers being born in the first half of 1848. By 1850 though, they had returned to Somerset, a second daughter, Lydia Ann being born in the village of Stanton Drew where the family was to stay for over forty years.

Stanton Drew Census 1851

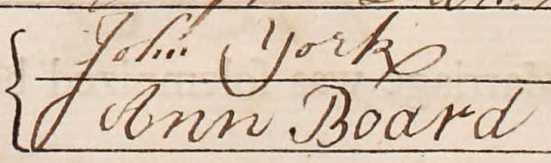

As can be seen Stephen now appears as Stephen Rogers, son of George and Phoebe. Besides the two girls there is George’s son, from his first marriage. By 1861 however a major development had taken place. The 1861 Census for Stanton Drew shows that the Rogers family had moved to the neighbouring village of Stowey (they were back in Stanton Drew by 1871) and grown with the addition of a son and two more daughters. Stephen was no longer with the family and had moved to Chew Magna, into the household of Samuel Gover, a blacksmith, whose apprentice he was. He had also reverted to the surname Bumstead (it appears as Bomsted in the 1861 Census).

We cannot know what happened to provoke this change – did Stephen fall out with his step-father or mother, or was he just asserting his independence. Interestingly he was baptised at Chew Magna (at the age of 16) on 18th March 1860, presumably whilst living there with the Gover family. He gives his father’s name as Stephen Bumstead, upholsterer. Was he only getting part of the story or perhaps guessing his father’s occupation? Later, on his marriage, he gave his father’s name as George Bumstead, Cabinet Maker – an interesting combination of the names of his biological & step fathers, although George Rogers was a carpenter rather than a cabinet maker.

By 1868 Stephen had moved to Bedminster and the next record we have of his life is the marriage to Louisa Peters who had also been living in Chew Magna. Louisa was a little older than Stephen (having been born on the 25th June 1842) and she was the mother of an illegitimate child. Her daughter had been born in Chew Magna in 1864 and registered under the name Rosina Fear Peters. It was common practice when a father would not (or could not) “do the decent thing” to give an illegitimate child the father’s surname as a middle name, and we can see that the father of Rosina was Samuel Fear (see here).

On the marriage certificate Stephen gave his address as North Street, Bedminster and Louisa was at West Street. Addresses at marriages are not always permanent residences – people used convenience addresses to be able for the Banns to be read – three weeks in a parish was enought for one to be considered a parish “member”. On the marriage certificate Stephen describes himself as a smith and on the Census of 1871, when the family were living at 29 Richmond Terrace, Bedminster he was still using the term Blacksmith. Rosina was given the surname Bumstead (or Bumpstead in the record).

A son, Frederick Walter, was born in 1879, and by the 1881 Census the family had moved to Canon’s Marsh. The address is difficult to read but appears to be “Offices, Heaven, John”. Stephen’s profession is now Engineer Driver for Saw Mills. A neighbour also worked in the timber trade and there were certainly timber yards on Canon’s Marsh in the nineteenth century, so it seems likely that the family lived “above the shop” in the company accomodation of John Heaven & Co. an established timber merchant in Canons Marsh. The progression to engineer was a natural one – many of the early journeyman engineers started their lives as blacksmiths, and Stephen seems to have stayed in the industry for the rest of his life, working on the stationary engines that powered the saws. On the census both Louisa and Rosina are recorded as Shirt Makers.

One of the many timber yards on Canon’s Marsh

Not many records survive of Stephen’s life, but one that does concerns the drowning in Bristol Harbour, of a quay labourer, Peri Ryan who fell into the water between the mission ship Bethel and the quayside in December 1886. The newspaper report of the inquest tells how Stephen, the only witness, heard moans and saw the deceased wedged between the ship and the quay and tried to help him, but could not hold on. The coroner expressed his opinion that there should be some sort of protection between the quay and the ship. This was carried out afterwards as the photograph of the site of the accident below clearly shows.

Bethel Mission Ship, St Augustine’s Reach

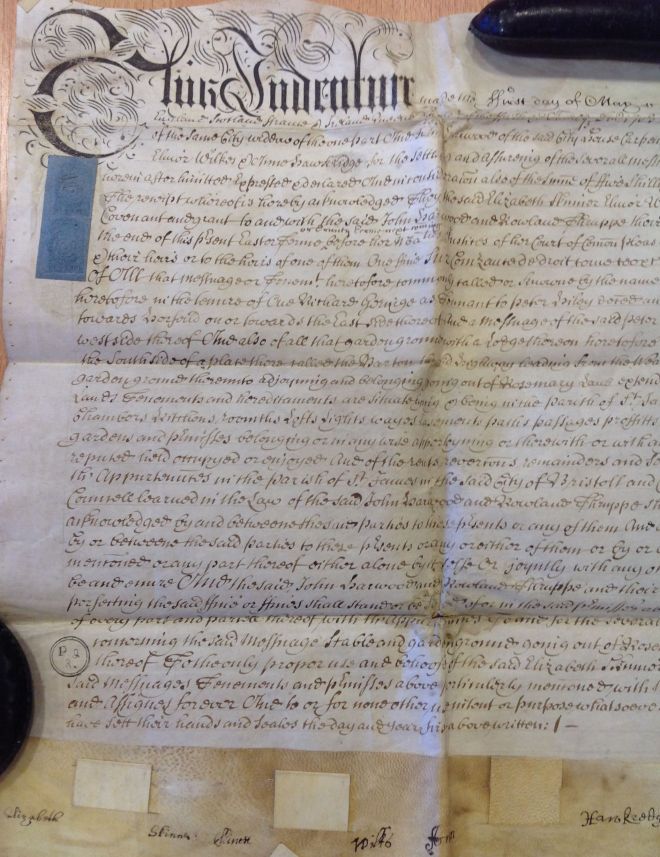

Stephen’s step-sister Phoebe Isabella had drowned in a boating accident at Bath on July 6th 1888 (see here) and just twelve days later, her father George Rogers travelled to Bristol to make his will in the offices of the solicitor William Watts. His estate, which totalled £220 was left to his wife Phoebe and thereafter to his surviving children. However there is a special bequest of £2.10s to his stepson, “Steven Bumstead”.

On the 1891 Census the family are still living in Canon’s Marsh and another son, Albert (actually George Albert, born July 3rd 1888, although he always seems to have been known as Bert) is present. Rosina had left however, having recently married John Roberts. Stephen is a Stationary Engine Driver and no occupations are recorded for Louisa or Frederick.

George Albert Bumstead c1898

Next to Bristol Cathedral stood the Church of St Augustine the Less (the Cathedral was St Augustine the Greater) and family tradition records young Albert as a chorister there. This was presumably before 1900 when the family moved back to Bedminster. Kelly’s Bristol Directory for 1900 has Stephen Bumstead at 2 Sheene Road, Bedminster, and from 1902 onwards shows the family at 176 York Road. In between, the 1901 Census has them at 1 Diamond Street (just off West Street). Although Stephen’s occupation remains the same, both Louisa and Frederick are recorded as Machinists (Wood Cutting). They now have a much fuller household; as well as Stephen, Louisa and the two boys, Louisa’s widowed mother, Elizabeth Peters, a niece, Lilian Chapman and three other boarders are recorded. Lilian and the other girl boarder, Rose Kruse work as cigarette packers (no doubt at Wills factory, just a few hundred yards away), whilst one of the male boarders, George Chapman, who worked as a railway stoker on the GWR was born in Bermuda in the West Indies, where his father was stationed in the army.

1 Diamond Street, Bedminster

The move to York Street, on the New Cut, facing the suburb of Redcliffe, was to be Stephen’s final one. He died on Christmas Day 1903 aged 59 of gastritis and was buried in a family plot in Arno’s Vale Cemetery. Louisa was to live on until 1923, when she too was buried in the grave. Their eldest son, Frederick was also buried there on his death in 1947.

Bumstead grave marker in Arnos Vale Cemetery

You must be logged in to post a comment.