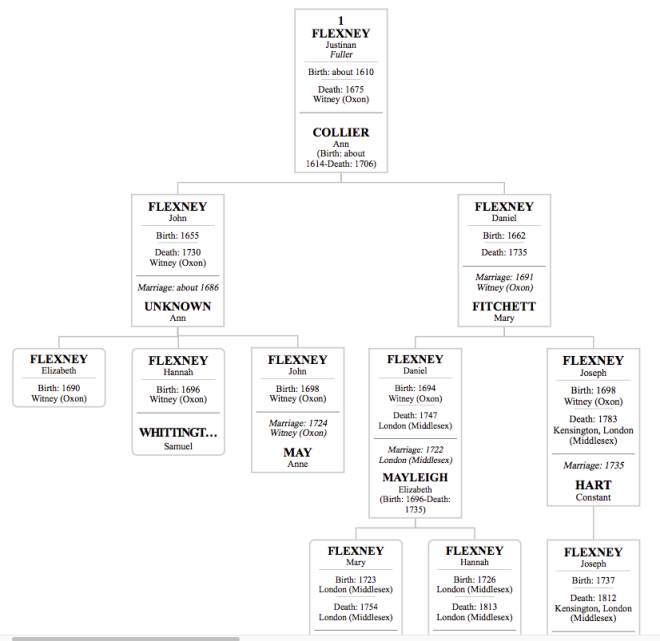

Simplified tree of the Flexney family

All my previous articles have concerned my direct ancestors or very closely related forebears. This one is different. In tracking down my Flexney family in Oxfordshire it was necessary to identify as many of the bearers of the name as possible in order to add or eliminate them from my line. In doing so I came across one branch of the Flexneys who prospered in the wooden trade, moved to London and whose story ended in a mixture of wealth and tragedy. I have decided to publish my findings here as a matter of interest and also to record part of the history of the wider Flexney clan.

Quaker Meeting House, Wood Green, Witney

There were many branches of the Flexney family in West Oxfordshire in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but one was pre-eminent in status. This was the line starting with Justinian Flexney, a fuller of Witney who died in 1675. His christian name indicates that his family may have originated in Stanton Harcourt, where there were at least three Justinian Flexneys in the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century, but a gap in the parish registers there makes it impossible to be sure. He married Ann Collier around 1640 (although I can’t find where) and had children baptised at St Marys, Witney in the 1640s. Strangely there is no mention of him in the Protestation Roll of 1641/2, although there are two Justinian Hicks listed. Now one branch of the Flexney family was known by the alias Hicks/Hix so it quite possible that Justinian belonged to one of these. A certain Justinian Flexney alias Hix was a party to two law suits in Chancery in the early 1600s and this may be his father; another identification may be the Justinian the younger, whose father died in 1634 in Stanton and who left a strange bequest to his son in his will (see here).

A Fulling Mill

Fulling (or in the south and west, tucking) is a process in the manufacture of cloth whereby the woven material was repeatedly hammered in a fulling mill, using a combination of chemicals (fuller’s earth) and soap in order to clean it and wash out any impurities, at the same time binding the fibres tighter. No doubt, with the importance of the cloth trade, especially the manufacture of blankets, fulling was a major industry in the area. Justinian died in 1675 and in his will (see here) he left his son John, three racks and three pairs of fullers shears as well as his house in Corn Street after the death of his widow, who had the use of it for life. An inventory lists all his possession including the shears, racks and furniture “att the mill”, which implies he must have leased it. There are small bequests for two sons-in-law, but no mention of his younger son, Daniel, then aged about 13.The burial register for St Marys, Witney is missing for the relevant period, but we can assume that Justinian was buried there, as in his will he states that to be his wish.

A document dated 1678, just three years after Justinian’s death names John Flexney as a fuller, and involved in the acquisition of a plot of land near Wood Green in Witney, which was to become the site of a Quaker Meeting House.This is the first indication that any of the family had joined the Society of Friends. By the start of the eighteenth century John and his brother Daniel were prosperous clothiers (cloth merchants) as well as being in the forefront of the Quaker community in Witney. Their names often appear at the head of any list in the minutes of the Monthly Meeting which organised the business of the Society. Their mother, Ann died in 1706 at the advanced age of 92 and in her will (see here) she left her son, Daniel the sum of £20 as well as her household goods which are “in his possession”; the will was drawn up in 1699 and shows that Ann was living with Daniel at that time. There is a proviso that the household goods should go to whichever of her children she was residing with at the time of her death. There are cash bequests for her daughters and a son-in-law and also to her sister, but the remainder of her estate is left to her eldest son, John. Ann was buried in the grounds of the Quaker Meeting House on Wood Green.

Around 1686 John Flexney married Ann although no record has been found. They were to have seven children of whom four, three girls and a boy, John survived to adulthood. Their youngest daughter, Hannah often appears on online trees as having emigrated to Pennsylvania and married one Thomas Rossiter; this is wholly incorrect for in fact she married Samuel Whittington and was named as Hannah Whittington in her father’s will of 1728. John and Ann’s final child was John who was born in 1698 and whose marriage to Anne May is recorded in the Quaker registers in 1724. John was described as a fuller, following the family trade, but his father was designated as a clothier in documents around this time. Anne May was the daughter of Edward May of Drayton in Berkshire (now part of Oxfordshire) who was a prominent Quaker also, and whose son, Edward had already moved to Witney and was a successful clockmaker.

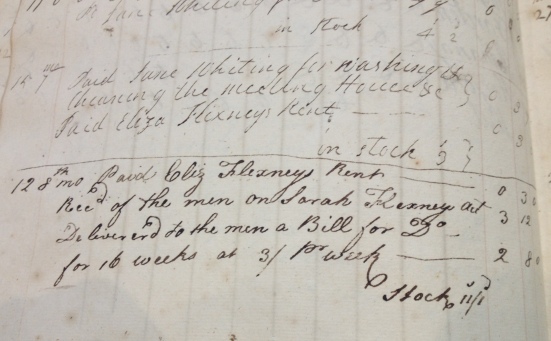

John Flexney senior made his will in 1728 and died late in 1730. Thereafter nothing more is heard of this branch of the family in Quaker or other records, with the exception of his daughter Elizabeth, (who was unmarried in 1735, aged around 45, and was still receiving money for her rent from Quaker charity funds into the 1760s) and an unnamed daughter of his son John, who were both mentioned in the will of their uncle.

Elizabeth Flexney’s rent paid by the Witney Quakers 1764

The family of John’s younger brother Daniel is rather better documented. Daniel was baptised at Cogges church in 1662, the youngest of the children of Justinian and Ann, who must have been around 47 years old when he was born. Quaker registers show him marrying Mary Fitchett on 4th July 1691 and he was already described as a clothier. The couple had six children of which two sons, at least, survived into adulthood: Daniel born in 1694 and Joseph in 1698. It appears that at some stage Daniel senior moved first to Widford, near Swinbrook and then to Burford where he leased a property in 1717 (The Swan) and, judging from the text of his will, carried on his business. He retained a freehold property in Witney which encompassed a messuage, yard and garden and a piece of “Meadow Grounds”.

Daniel made his will on October 18th, 1735 and was by this time, blind (for transcription see here). It was drawn up and witnessed by Joseph Besse, the noted Quaker writer who was later to compose “A Collection of the Sufferings of the people called Quakers”. Besse noted in an appended declaration that he had known Daniel for several years and that he also drawn up a private schedule which was to be kept by Besse until delivered up to the Court for probate. Besse notes in the will and declaration that Daniel had dictated both documents to him and approved of both on having them repeated to him. Together with a codicil made three weeks later (and to which Joseph Besse does not seem to be a party) these documents give an interesting insight into the Flexney family and Daniel’s religious convictions. Apart from the normal family bequests of cash, ranging from £5 to a niece up to £250 each to the two daughters of his son, Daniel, he left his freehold property in Witney and all the remainder of his estate to Daniel, appointing him his executor. The younger son, Joseph recieved the leasehold house in Burford and the “giving and forgiving” of a debt of £1000 which was outstanding. This gives some indication of the wealth of the family.

One section of the will and the “secret” appendix relates to the desire of Daniel to establish the survival of a charity bequest as well as to arrange the printing of some papers which he had written on religious matters. The latter are described as a manuscript containing “a paper…..against Plays, another against Games and Whitsun sports so called and also a paper of mine containing advice to Magistrates to suppress Vice and Immorality”. These were to be printed and distributed “among my Neighbours acquaintance and such as have heretofore been my servants or employ’d by me in and about Burford and the adjacent places”. The charity bequest was in the form of £100 put out at interest, and for the interest thereon to be distributed by Trustees nominated by the Witney Quaker Monthly Meeting.

The codicil to Daniel’s will arranged that in the absence abroad of his son Daniel, the younger son Joseph was to be his executor and bound him to carry out the terms of the will. It would appear that Daniel senior was fast approaching death and was concerned that probate might be delayed if his eldest son did not return in the near future. The codicil was dated November 11th 1735 and the will was proved, naming Joseph as the executor on December 4th, so we must assume Daniel senior died soon after the date of the codicil. There is no record of his burial. Was he aware that his son Joseph had married in an anglican church six months earlier one wonders? Joseph’s bride was Constant Hart and in the register of St James, Newbottle, Northamptonshire the couple are both described as “of Burford in….Oxfordshire”; the marriage was by licence. Constant was baptised in 1708 in the church at Burford, so may have remained an Anglican. Only one child of this marriage is recorded – another Joseph born in 1737. Following the terms of his father’s will, Joseph took on the property in Burford and extended the lease in 1735, for a further 21 years, agreeing to spend £100 in repairs. Joseph continued his father’s business as a clothier but also invested elsewhere. In 1737 he was a partner in providing capital for a paper mill at Upton, just upstream of Burford. It may well be that Joseph expanded his business into London as did his elder brother, Daniel (see below) for in an Old Bailey trial of 1737 the accused is indicted for stealing 5 yards of cloth belonging to Joseph Flexney in the parish of St Leonard, Shoreditch.

The younger Joseph married Martha Taylor of Shutford in a ceremony recorded by the Monthly Meeting of Burford on July 11th 1759. Both father and son are described as “Clothers” and both sign the certificate. There is no mention of Constant so it may be assumed she had died by then. A year later, Joseph junior was a witness at the marriage of his cousin, Hannah (see below), but records of the two Josephs are sparse after that. Joseph senior died at Burford on January 3rd, 1783 and was buried, alongside his family no doubt, in the Burial Yard of the Meeting House in Witney. The instruction to the gravedigger bears the remark that Joseph “stood disowned” so had presumably broken with the Quaker community.

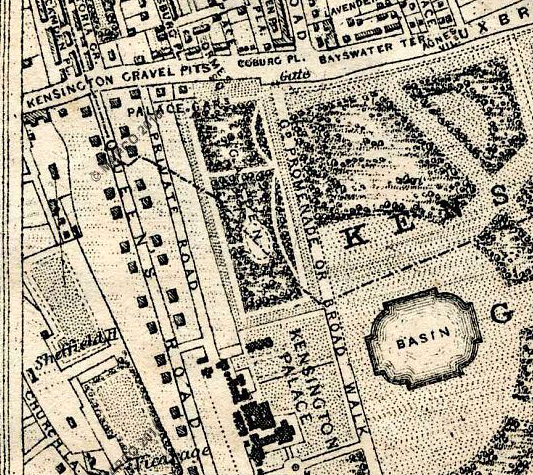

Joseph junior and his wife Martha moved to London at some stage, for the Land Tax records shows Joseph living in Kensington from 1797 onwards and when Martha was buried at Hammersmith in 1807, her address was Kensington Gravel Pits. This was just north of Kensington Palace, and was a far more prestigious residence than it sounds. The same address is given on Joseph’s burial five years later, with the added comment “not a Member”. So it seems both Josephs had cut ties with the Society of Friends.

Location of Kensington Gravel Pits

In contrast, Daniel Flexney the younger, who was born in 1694, maintained his Quaker faith throughout his life, as far as the records show. As we have seen above, he was not in England in 1735 when his father made his will. It is most likely that he was in Pennsylvania where he had many trading connections. The first mention of him comes upon his arrival at Philadelphia in 1718. A certificate from the Witney Monthly Meeting, dated August 11th 1718 was presented there on September 26th and describes him as unmarried and the son of Daniel Flexney of Burford. It was signed by his father, uncle and cousin, John. It would seem that Daniel spent some time in America, making trading contacts and buying land. He certainly struck up a relationship with the Phildelphia merchant John Reynall, who for many years acted as a factor for Daniel and was involved in numerous transactions with him. One concerned the commissioning and building of a ship “The Mary” which was constructed in Philadelphia on behalf of Daniel (for details see here). There are many references to Daniel, his trading connections and law suits on the internet should anyone wish to delve deeper into his career.

Daniel was certainly back in London, living in Lime Street, in 1722 when he married Elizabeth Mayleigh, the daughter of an apothecary, on June 4th at Devonshire House. His father and brother were present at the Quaker ceremony and signed as witnesses. Daniel junior is already described as a merchant. The couple were to have six children, all born in London, but sadly only two survived childhood, their daughters Mary and Hannah. Looking at the records of the childrens’ births we can see that Daniel and Elizabeth lived at first in Camberwell, but later moved to Bishopsgate Street in the city. Daniel is sometimes referred to as an apothecary like his father-in-law, so presumably he carried on this profession whilst maintaining his trading contacts. Certainly one document of 1737 complaining of his business actions refers to him as an apothecary, at the same time mentioning that he owned a ship called “The Elizabeth” (see here); It also refers to him living for some years in Jamaica for the sake of his health.

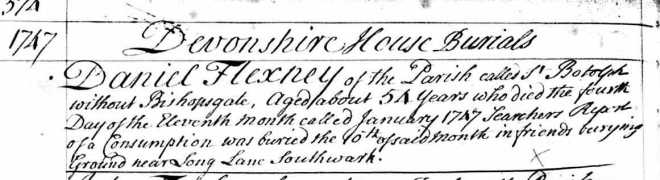

Daniels’s burial in the Quaker register for Devonshire House

Daniel’s wife Elizabeth died in 1735 and was buried at the Long Lane Burial Ground in Southwark; Daniel died on January 4th 1748 (1747 Old Style) and was buried in the same place. The burial record notes that he died “of a Consumption”. His will dated December of the previous year leaves all his estate, including his property in Witney, equally to his two daughters, making them joint executrices; he makes it plain that Hannah the youngest was to act as such even though she was under the age of twenty-one. He must have been a wealthy man, his address at the time of his death was New Broad Street which consisted at the time of substantial brick-built houses constructed in the 1730s, and so his death left his daughters (with their already generous legacies from their grandfather) rich heiresses. Mary the elder of the two married William Hyde, a Corn Factor at the Devonshire House Meeting on September 1st 1748, and twelve years later her sister Hannah married William’s brother, Starkey Hyde, a Stockbroker in the same place. Both couples went on to have several children and I had intended to finish my account at this point, but in researching details of when the two Flexney sisters died, I discovered the tragic story of the Hyde family.

William and Mary Hyde appear to have had only two children, Richard (born 1749) and Elizabeth (born 1751) before Mary’s early death (of a “Consumption” like her father) in 1754. Elizabeth is probably the child whose burial is recorded, aged 12 in 1764; she too died of consumption. Starkey and Hannah had four children, but the three eldest (all boys) died in infancy, leaving a daughter, Mary who was born in 1768.

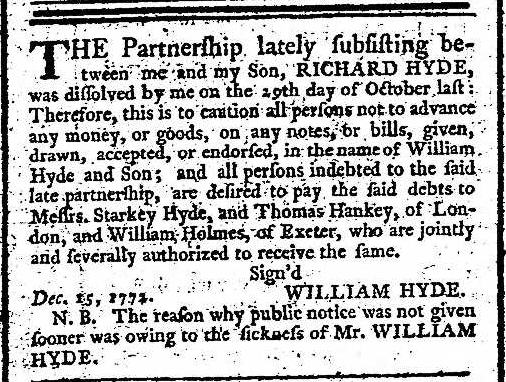

Dissolution of the partnership

William Hyde and his son Richard had gone into partnership, presumably as brokers, but this partnership was dissolved by William in October 1772 and an advertisment placed in the Middlesex Journal warning others not to advance any money against bills or notes drawn on the partnership. It is noted that the two month delay in placing the advertisment (it is dated December 15th) was caused by the sickness of William Hyde. Further evidence of the falling out between father and son is given in the will which William drew up in 1775; now retired from the Corn Exchange, living in Kingston upon Thames and styling himself a Gentleman, William left his only surviving child “one Shilling and no more”. The bulk and remainder of his estate (after some cash bequests to sister and cousins) he left to his brother, Starkey.

On June 28th 1780 Richard Hyde was indicted at the Old Bailey on a charge of breaking the peace and riot and was tried before a jury (for a transcription of the trial see here). The crime in question took place on June 6th and involved the breaking into and ransacking of the house of one Richard Akerman, which was later set fire to and destroyed. This action, carried out by a mob of several hundred, was part of the Gordon Riots which saw many government properties attacked, as well as much private property. Several witnesses confirmed that Richard Hyde had been one of the first to enter Ackerman’s house. The evidence and statements taken at this trial give an insight into the troubled world of the Hyde family. One medical witness, Dr Munro states that he knew the family and had attended William Hyde in October 1772 (the date of the ending of the partnership) when he was “in a state of insanity”, and although his son Richard was perfectly sane. Yet the following year Munro attested that he had found Richard too in a state of insanity. Another witness stated that he believes William was, at the time of the trial, in a state of confinement, and many others provide evidence that Richard was at times clearly insane and at others, quite normal and sensible. It further emerges that his uncle Starkey, although not insane was “extremely low and melancholy”. It seems as if William gave his son an allowance of a guinea a week although at one point Richard (whose comments pepper the trial) claimed that this had been reduced to half a guinea as “I kept two women instead of one”.

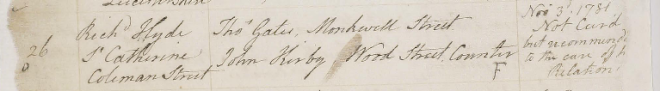

The counsel for the crown finally moved that Richard be found not guilty as long as he could be held in confinement, and the Judge agreed and released him into the custody of Richard Kirby of the Wood Street Comptor, a small debtors prison (Newgate, the Clink and other prisons had been badly damaged by the Gordon rioters). His illness and that of his father would probably be diagnosed as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia today, but in the eighteenth century it was merely classed as insanity and confinement was the only recourse. If William was also confined, it was presumably in comfortable circumstances, owing to his wealth, and overseen by his brother, Starkey. However, in 1781 Starkey died and we may assume Hannah his widow continued his role in the family’s trials. It is a fact that William did not make a new will following his brother’s death, so perhaps was incapable of doing so. In August 1780 Richard had been transferred to the Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam) which was the main destination in London for anyone suffering from mental health problems. It has a fearsome reputation, but some good work was also carried out there into restorative therapy. However in Richard’s case an annotation in the margin of his admission record states “Nov 3rd 1781, Not Cur’d but recommended to the care of his Relation”. This must be Hannah his aunt.

Admission register for Bethlem Hospital 1780

William Hyde died in 1785 and administration of his estate was, quite amazingly, granted to Richard “his natural and lawful son”. Apart from Starkey there were two other executors named in the will but they renounced their position. Possibly this was a period of remission for Richard, or more likely, his aunt was somehow controlling his actions. In any case, Richard did not live long to enjoy his new-found wealth; he died on 25th February 1787 “of a Decline” being just under the age of 37. He was buried where most of his family had been interred, at Long Lane Burial Ground, the record noting that he was not a member of any Meeting, but the burial was “granted at the request of Hannah Hyde”.

His will makes interesting reading; there is an affadavit attached, being the statement of Robert Gramond, Gentleman who knew Richard and had seen him sign his name. He confirms that the document is in Richard’s hand and the signature is his. The will itself is a more personal document than the formulaic type usually encountered. Following the normal form of confirming that he was sound of mind, Richard starts by saying “I resign my life to him who gave it with as little regrett as a young man naturally fond of this World can be expected to do”. He then continues with a request that he be buried as near his father in Long Lane Ground as is possible. He requests that a couple of specific debts are paid using remarkably modern language by saying that one loan was made “at a time I really wanted it”. The main beneficiary of the will is a Betty Eaton, wife of Wall Eaton, “now living at Dr. James Shattens at Bethnal Green”. From what little I can discover, I think this was another place of confinement for lunatics. Richard makes it explicit that Betty’s husband is to have no benefit from this legacy. He adds that he should perhaps have left his money to his aunt Anna (the sister of William and Starkey) but concludes she is old and infirm and that his aunt, “the widow”, namely Hannah, will look after her “as long as she lives as her Daughter will immediately come into possession of so good a fortune”. So little love lost there I think. Richard names as his sole executor “my dear and worthy friend Dr Henry Saffory Surgeon of Devonshire Street”, who in due course obtained probate. It may be worth noting that Henry Saffory was a leading expert in the treatment of venereal disease.

Richard’s will is a sad document, perhaps written by someone who had no direct control over his assets, but was, nevertheless determined to see that they went where he desired. For a will it is a very personal document and is moving, in a way not often encountered.

There is very little to add to the story of the Hyde family. Richard’s spinster aunt Anna Hyde died in 1789 and was also buried at Long Lane, and his other aunt, Hannah died in 1813, her residence given as Lower Grosvenor Street (or Place in one document), Pimlico. She too was buried with all her family at Long Lane. There appears to be no will for her and I can find no further trace of her daughter Mary.